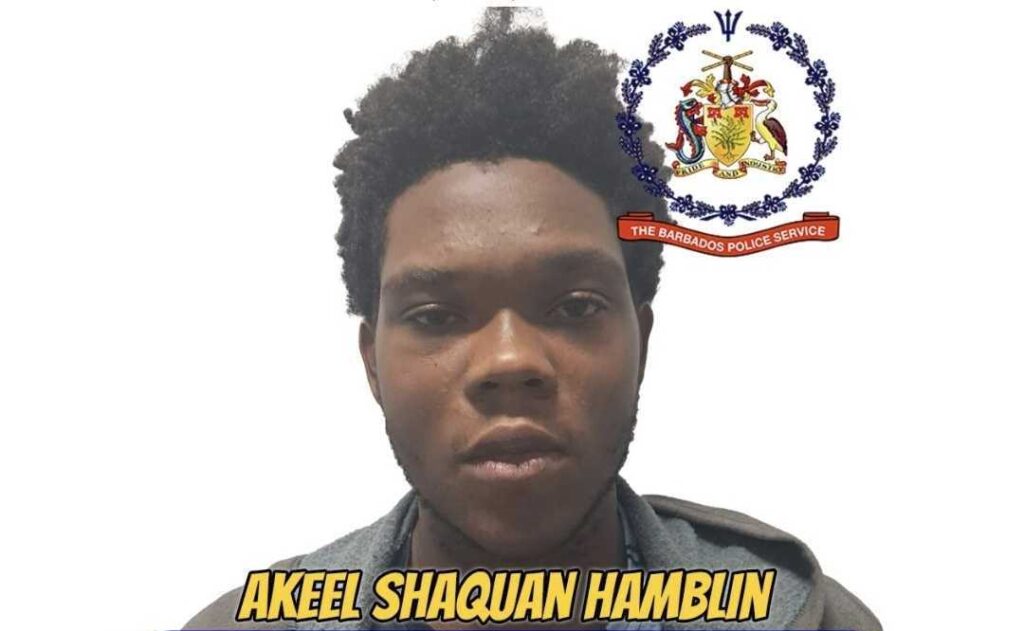

A short video clip showing people reacting to Jesus rising from the dead recently made the rounds online — absurd, hilarious, and shared widely. Around the same time, images of ‘persons of interest’ spread across WhatsApp long before any official statement or confirmation from authorities. That’s media too. It makes people listen, laugh, feel, react. But it also teaches what to care about, what to ignore, what to believe.

Media has never been neutral. But now, its speed and scale have changed the game. We live in a world where media no longer just reflects reality — it manufactures it. Platforms decide what matters before there’s even time to think. Deepfakes distort truth. Newsrooms shrink while algorithms scale.

Media houses, including this one, must ask harder questions. We are not the only gatekeepers anymore. Influencers, citizen journalists, content creators all shape the information ecosystem. Some fill critical gaps. Others deepen confusion. And without shared standards or trust, we’re left guessing what’s real.

A few weeks ago, John Oliver aired a segment on “AI slop”—bot-generated content stitched together for clicks. The New York Times followed with a question: Can you believe your own eyes anymore? The answer? Not without context, clarity, and a healthy dose of doubt.

Here in Barbados, we are not exempt. Generative AI is already in newsrooms. Sometimes, it’s used out of necessity. In small newsrooms, relentless cycles make speed a matter of survival. But we can’t confuse survival with strategy. What’s lost when we automate the work of thinking? What values are embedded in that speed? And who pays the price?

Even this editorial—was it written by a person or a machine? Does it matter? That pause — that doubt — is the point.

Because despite what tech boosters say, generative AI doesn’t “hallucinate” or “think.” It recombines what we’ve trained it on at scale. In the absence of regulation, the burden falls unfairly on the “user”, who is expected to navigate a system they didn’t build. But structural issues can’t be solved with personal vigilance. The real power lies with those who design the systems, profit from the content, and shape the rules.

Today’s media ecosystem isn’t built for public service, it’s built to optimise engagement, emotion, and scale. And it’s not just misinformation. It’s the collapse of context itself—the erosion of meaning, nuance, and memory.

This is why media literacy matters. Not just to spot fake news, but to understand how media works on us, often without us noticing. We realise the cost too late: in polarisation, miseducation, cultural loss.

So who has the rights? Who carries the responsibility?

Governments must act like they do. That means clear data governance, not vague digital slogans. It means mandatory media literacy in schools. It means enforcing accountability when tech giants monetise culture while dodging regulation.

And media houses can’t treat virality or AI as neutral tools. We must build standards for editorial use, cultural care, and labour dignity. Because media teaches, even when we’re laughing, scrolling, zoning out. The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill wasn’t just an album title. It was a warning about invisible instruction. Media always teaches. The only question is: who decides the lesson?

We already have the tools. The United Nations has published global principles on digital rights. The Cybercrime Bill in Barbados is being debated. There are policy templates, climate data on digital waste, and research on regulatory frameworks. As we ask for solutions, we must stop pretending they don’t exist. The tools exist. What we lack is resolve.

The post Media in the age of AI appeared first on Barbados Today.